#11 なぜ哲学を学ぶのか?Why Philosophy?

A lot of the teaching done in schools is teaching towards a test. There are specific contents that students need to learn and remember. In a typical physics class, for example, students are presented with a formula for calculating velocity; the goal of the class is for them to remember the formula and be able apply the same formula novel situations.

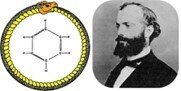

We tend to think of science in similar terms, as the recording and analysis of facts. But this is incorrect; or at least, a very limited understanding of what science is. For example, there is a crucial role for imaginative speculation in scientific discovery. When August Kekule discovered the chemical structure of benzene*, he did so by visualizing an image from a dream – a snake with its tail in its mouth – and synthesizing this with his prior understanding of benzene. His discovery shows that imagination and scientific understanding are inseparable.

Our school has a long history as a science /STEM school, with a strong engineering background. Therefore, as part of our mission, we need to nurture not only analysis, memorization, and the understanding of experimental techniques, but speculation, risk-taking, and a willingness to take imaginative leaps.

Philosophy and literature have an important role to play in our school curriculum. They help develop the curious, playful and imaginative aspect of learning at the same time as honing analysis skills. Questions about the meaning of concepts (in philosophy) or the meaning of stories (in literature) are inherently ambiguous, open to multiple interpretations, limited only by the evidence in the text or the logical connections between ideas considered.

These classes allow students to practice two skills that tend to be neglected in Japanese education - idea generation and explanation. Philosophy class gives students a space to think freely about a topic and to generate lines of thinking, following their interest in a topic and formulating problems in their own language, on their own terms, without the constraints of memorization.

In philosophy, students learn not only that they can say things without being personally judged, but that explaining their ideas is fundamental to understanding them, and further, that until they attempt to explain their thinking, they may not be able to see what is problematic about it. If the question is “What is time?” then any first answer to this question is likely to be partial, incomplete – in need of further revision and improvement. And if all ideas are open to question, then students don't need to worry about making mistakes.

Both philosophy and literature classes give students repeated practice generating ideas and trying to say what they mean. They come to see that we can't be satisfied with our first intuitive thoughts on the topic, but should explore why we think what we think, and consider whether those beliefs are based on good reasons or evidence. They promote both the analysis of given information and the synthesis of new ideas. They are, consequently, of great value to our school’s mission of promoting science.

As Albert Einstein said, "Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world."

(日本語訳)

学校で行われている教育の多くは、試験に備える教育です。生徒が学び、覚えるべき内容が決まっています。例えば、物理の授業では、速度の計算式が提示されますが、その式を覚えて、同じ式を新しい状況に適用できるようになることが、授業の目標です。

科学もこれと同じように、事実を記録し、分析するものと考えがちです。これは間違いであり、科学について限定的な解釈です。例えば、科学的発見には、想像力豊かな思索が欠かせません。ケクレは、夢の中で見た蛇が尻尾をくわえている姿をベンゼンの化学構造と結びつけて、ベンゼンの化学構造を発見したと言います。彼の発見は、想像力と科学的理解が切り離せないものであることを示しています。

本校は、エンジニア分野、科学の分野、STEM教育に長けた大学の附属校として長い歴史を持っています。分析、暗記、実験技術の習得だけでなく、推測、リスクテイク、想像力を膨らませる生徒の意欲を育むことが私たちのミッションの一つです。

哲学と文学は、学校のカリキュラムにおいて重要な役割を担っています。分析能力を磨くと同時に、好奇心や遊び心、想像力などを伸ばすのに役立ちます。哲学における概念の意味や、文学における物語の意味に関する問題は、本質的に曖昧であり、複数の解釈が可能であり、テキストにある証拠や考察されたアイデア間の論理的なつながりによってのみ制限されます。

このような授業は、日本の教育で軽視されがちな「発想力」と「説明力」を鍛えることができると考えます。哲学の授業では、暗記という制約を受けずに、テーマに対する興味に従って自由に考え、自分の言葉で、自分の言葉で、問題を定式化し、思考の筋道を生み出す場を提供します。

哲学では、個人的な批判を受けることなく物事を言えるだけでなく、自分の考えを説明することがそれを理解するための基本であり、さらに、自分の考えを説明しようとしない限り、それの何が問題なのかが分からない場合があることを学びます。もし「時間とは何か」という問いであれば、この問いに対する最初の答えは、部分的で不完全なもの、つまりさらなる修正や改良を必要とするものになる可能性があります。そして、もしすべての考えが質問に対してオープンであるなら、学生は間違いを犯す心配をする必要はありません。

哲学や文学の授業では、生徒たちはアイデアを出し、それが何を意味するのかを述べる練習を繰り返し行います。そのテーマについて、最初の直感的な考えで満足するのではなく、なぜそう考えるのかを探求し、その信念が正当な理由や証拠に基づいているかどうかを検討する必要があることを、理解するようになるのです。また、与えられた情報の分析と新しいアイデアの合成の両方を促進します。その結果、科学を推進するという本校の使命にとって、大きな価値を持つことになります。

アルバート・アインシュタインはかつてこう述べています。

「想像力は知識よりも大切だ。知識には限界があるが、想像力は世界を包み込む。」